前回エントリでクルーグマンのインフレに関するツイートを紹介したが、その後にクルーグマンはその件についてさらにツイートしている(H/T タイラー・コーエン)

Some further thoughts on inflation and what to do next. Inflation has of course come in much higher than Team Transitory predicted — the Fed was predicting only 2.4% PCE growth as late as March. So the inflation worriers have in a way been vindicated, but ... 1/

The details of what's happened are very different from what they predicted early this year. 2/

Olivier Blanchard offered an admirably clear exposition: stimulus would lead to a huge surge in demand above capacity 3/

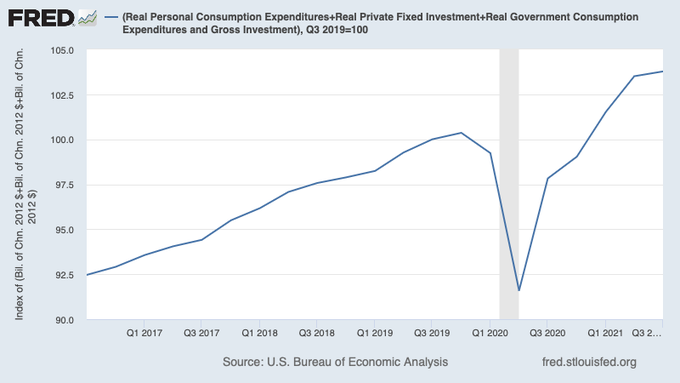

But demand *hasn't* risen all that much: real domestic final spending up 3.8% in 2 years, roughly consistent with normal potential growth 4/

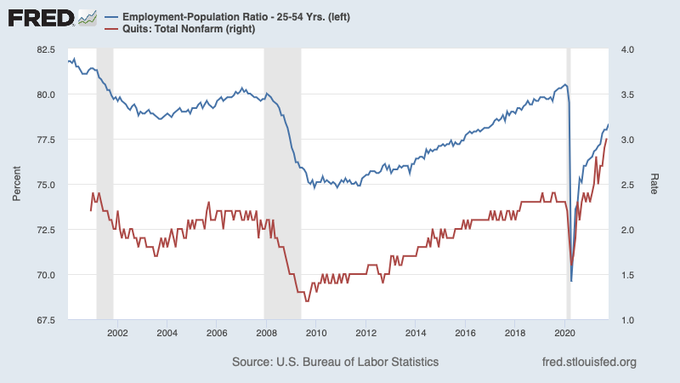

What's happened instead is that potential is lower than we would have expected, thanks to Great Resignation; employment still low but all signs say labor market very tight 5/

So economy may be overheated given that. But everything we knew before said that this should have only a modest effect on short-term inflation 6/

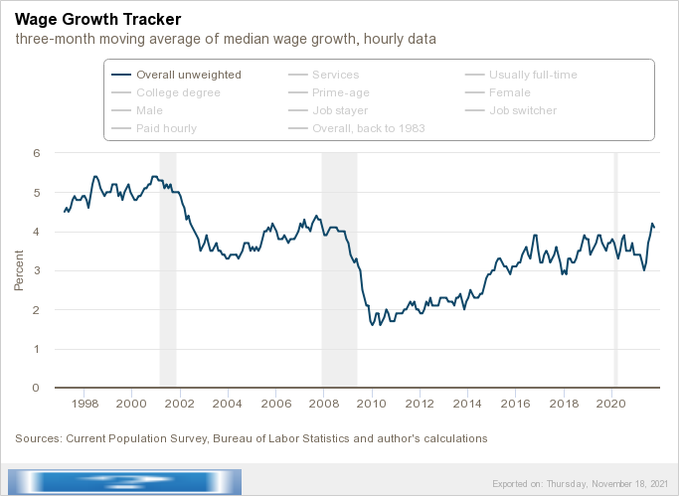

In fact, labor market tightness seems to be only a modest contributor to overall inflation so far 7/

If you believe the BIS, supply-chain issues and resulting bottlenecks are a much bigger factor 8/

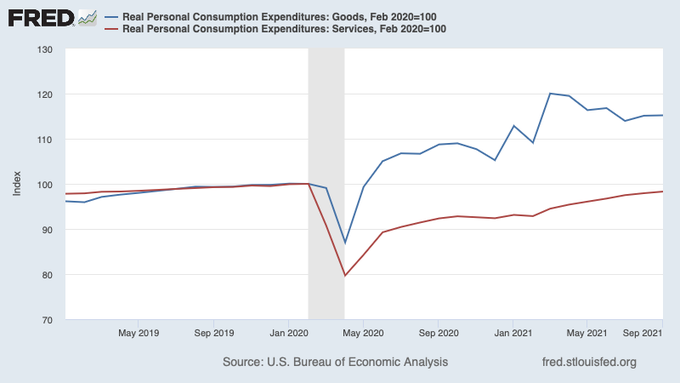

These largely reflect not so much overall level of demand as its skew toward goods as opposed to services — which I don't think anyone saw coming 9/

Historical interpretation aside, what does this say about future policy (it's all about the Fed now)? Should the Fed tighten to bring inflation down? 10/

The problem with this argument is that to the extent that this is about bottlenecks, you're basically saying that the whole economy should be held back by the most constrained sector 11/

This reminds me of people who argued for monetary tightening in 2008 because of a commodities boom; to caricature only slightly, it's the idea that the whole US economy should be limited by port capacity at LA 12/

That said, if the Great Resignation persists and/or if there start to be hints of expected inflation feeding into price-setting, the Fed may want to raise rates, and shouldn't set down markers that it definitely won't.13/

If I have a difference with Jason Furman here, it's about nuance not big picture14/

Basically, however, don't panic. This isn't 1973, when Nixon's political business cycle interacted with the oil shock to produce stagflation. It's a much more excusable and manageable problem 15/

(拙訳)

インフレと、次に何をすべきかについてもう少し考えてみる。もちろんインフレは、それが一時的と考えていた人々の予測よりも高くなった――FRBは3月時点でもPCEは2.4%しか伸びないと予測していた。従って、インフレ懸念はある意味で裏付けられた。しかし・・・

実際に起きたことの詳細は、インフレを懸念していた人々が今年初めに予測していたものとはかなり違っていた。

オリビエ・ブランシャールは見事なまでに明確な解説を提示していた。即ち、刺激策は生産能力を上回る需要の大きな増加をもたらす、と。

www.piie.com

しかし需要はそれほどは伸びなかった。実質国内最終支出は2年間で3.8%伸びたが、その伸びは概ね通常の潜在成長率に見合ったものだった。

代わりに起きたことは、大量退職のせいで潜在生産力が期待以下にとどまったことだった。雇用水準は未だに低いが、すべてのシグナルは労働市場が非常に引き締まっていることを示している。

それからすると、経済は過熱しているのかもしれない。しかし我々が前もって知っていることすべてに鑑みると、このことは短期のインフレに小幅の影響しか与えないはずである。

*1

実際、労働市場の逼迫は、これまでのところ、総合インフレには小幅に寄与しているに過ぎない。

BISを信じるならば、サプライチェーン問題とそれによるボトルネックの方が要因としてずっと大きい。

www.bis.org

これは、需要がサービスではなく財に傾斜し、全体水準がそれほど増えなかったことを反映している――こうなると予想していた人がいたとは思われない。

過去の解釈はともかく、これが将来の政策にとって意味することは何だろう(今やすべてFRBの問題だ、ということか)? FRBはインフレ率を下げるために引き締めるべきなのだろうか?

この主張の難点は、これがボトルネックの問題である限りにおいて、最も制約された部門によって経済全体が抑制されなくてはならない、と基本的に言っていることになることだ。

この話は、2008年の商品相場上昇を受けて唱えられた金融引き締め論を思い起こさせる。少しだけ戯画的に言えば、米国経済全体がロサンゼルスの港湾の稼働能力で制約されるべき、という考えというわけだ。

とは言え、もし大量退職が継続したならば、ないし、予想インフレが価格設定に反映される兆候が見え始めたならば、FRBは金利を引き上げたいと思うだろうし、絶対引き上げないなどと言うべきでもない。

以下の論文でジェイソン・ファーマンが言っていることと僕の考えが違う点があるとすれば、ニュアンスの話で、全体像についてではない。

www.piie.com

とにかく、基本的にはパニクらないことだ。今は1973年ではない。当時はニクソンの政治的な景気循環がオイルショックと相互作用し、スタグフレーションがもたらされた。今回の問題はもっと言い訳の効く管理可能な問題だ。