引き続き経済学者のインフレに関するツイートねた。今回はリカルド・ライスのツイートを紹介してみる(H/T 本石町日記さんツイート経由のRyo Takagiさんツイート)。

** The “macro” view on 2021 inflation

Since March 21, I've given many public lectures on inflation. All of them included the slide below (most recently at the Jahnsson prize lecture)

Tldr: every macro theory of inflation correctly predicted the high inflation that we have seen

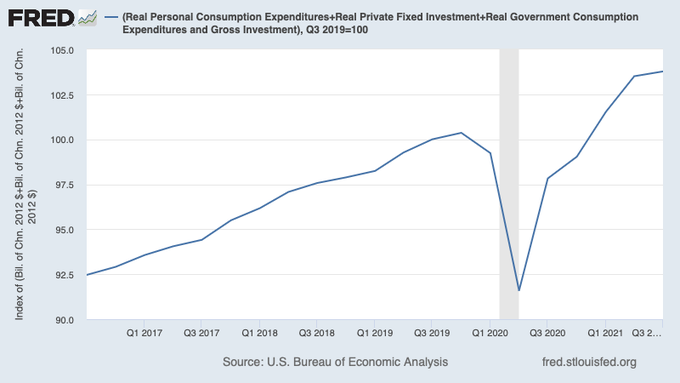

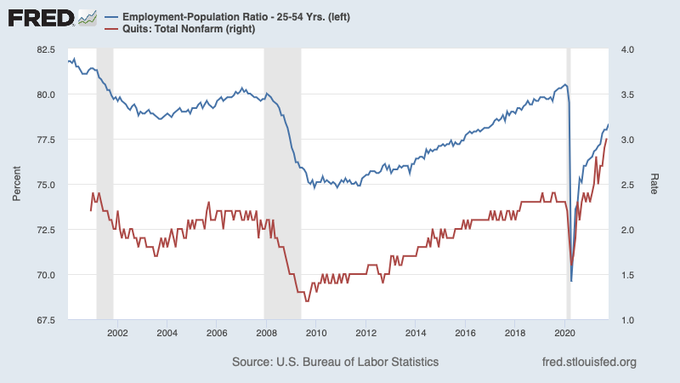

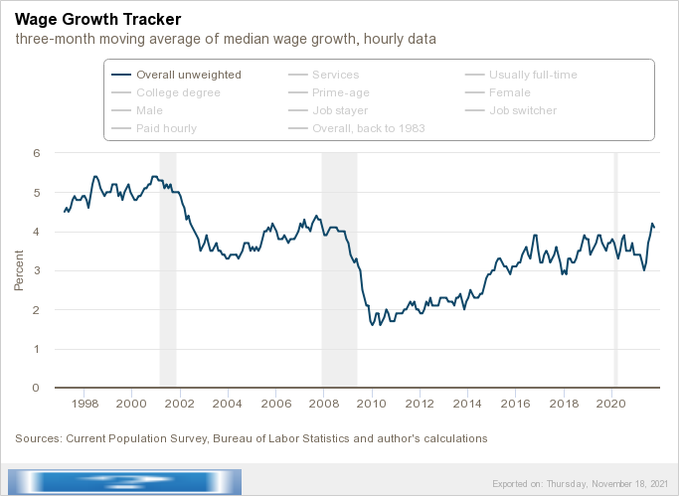

The 1st theory (Phillips, Keynesian) sees inflation as following from the closing of gaps in labor and product markets. Given how quickly the economy was rebounding already at the start of the year (and partly due to fiscal stimulus), inflation was expected to rise in 2021.

The 2nd theory (Wicksellian) sees inflation as resulting from interest rates being too low relative to a “neutral” benchmark. With CBs committing to keep interest rates at minima until 2022 and beyond, most rules (including Taylor's famous one) would put it below that benchmark.

The 3rd theory (monetarist) points to the record-high level of bank deposits that resulted after lockdowns and large fiscal transfers. With the economy reopening, this "money” would chase “goods” raising prices

The 4th theory (fiscalist) looks at fiscal variables. With public debt at record high levels, and the large deficits resulting from the January fiscal plan, the likelihood that fiscal concerns would dominate policy and drive inflation, was surely at a high in 2021.

The 5th theory (commitment) says that ultimately inflation is what the CB chooses it to be, so look at the CB objectives and te stations. The Fed and ECB mission reviews clearly made them become more tolerant of higher inflation relative to other goals.

The 6th theory (new Keynesian) looks at optimal trade-offs between employment and inflation. With supply shocks, the CB will tolerate higher inflation in order to have a speedier recovery.

It is quite rare in economics that every single major theory points in the same direction.

When it happens, we can’t learn which theory is right. But I was unusually confident in saying early in in 2021 that inflation would be high, even before the data was showing it.

Each theory predicts adjustments in different prices moving at different speeds. Each makes a different guess of how high inflation will rise, and which micro features (e.g., slopes of curves, expectations) are central. Data, micro and macro, was very helpful in these two senses

But, in the first half of 2021, if you only looked at micro price "big" data, you would get distracted by: different indices, changing baskets, base effects, measurement errors. You might even (as some did) question if inflation was coming. Theory set you straight.

The macro view of inflation is not *only* about stimulus. @LHSummers focussed on that in his early writings, but the point was broader. When I showed the slide at the diverse audience in the @NBERpubs macro annual in April, some preferred some theories.

Austan Goolsbee

2) Does the strictly macro view of inflation that says it’s mainly about size of stimulus in early 2021 not imply that one year later when that becomes the baseline, the fiscal situation turns highly deflationary?

Note that across theories, both the inflation and its ultimate cause, are not necessarily bad. In some, inflation was a needed sacrifice or even good. But what I've been writing here against is what I've called "team no pasa nada". Hopefully, that is now an untenable stance.

What about inflation beyond 2022? Here theories disagree, data will supports some and reject others, debate is needed, uncertainty is inevitable. As is normally the case.

(拙訳)

2021年インフレについての「マクロ的」見解

3月21日以降、私はインフレについて多くの公開講演を行ってきた。それらすべてで私は以下のスライドを示した(直近はヤンソン受賞講演*1)。

今北産業:インフレに関するすべてのマクロ理論が、我々の目にした高インフレを正しく予測した。

第一の理論(フィリップス、ケインジアン)は、インフレを、労働および生産物の市場でのギャップが閉じることに伴うものとしてみている。経済が今年初めに既にどれだけ急速に回復していたかに鑑みると(そして財政刺激策の寄与もあり)、インフレは2021年に上昇すると予想されていた。

第二の理論(ヴィクセリアン)は、インフレを、金利が「中立的」ベンチマークに比べ低過ぎる結果として生じるとみている。中銀が2022年まで、およびそれ以降も金利を最低限に留めると約束していることから、大半のルールは(テイラーの有名なものも含め)金利はそのベンチマーク以下になるとしている。

第三の理論(マネタリスト)は、ロックダウンと大規模な財政移転の結果として、銀行預金が史上最高水準になっていることを指摘する。経済が再開すれば、この「マネー」は「財」を追い掛け、物価を引き上げる。

第四の理論(財政主義)は、財政変数を見る。公的債務が史上最高水準にある上に、1月の財政政策案から大規模な財政赤字がもたらされることから、2021年に財政懸念が政策面で支配的になりインフレをもたらす可能性は確かに高かった。

第五の理論(コミットメント)は、インフレは最終的には中銀が選択したものになるので、中銀の目的と立ち位置を見よ、と言う。FRBとECBの目的レビューは、明らかに他の目標に比べ彼らを高インフレに寛容にしている。

第六の理論(ニューケインジアン)は雇用とインフレの最適なトレードオフを見る。供給ショックにより、中銀は回復をより速くするため高インフレを許容する。

経済学において主要な理論すべてが同じ方向を指し示すことは極めて稀である。

そうなると、どの理論が正しいかを知ることはできない。しかし2021年初頭に私は、データでそれが示される以前だったにもかかわらず、インフレが高くなるだろうと言うことに常にない自信を感じていた。

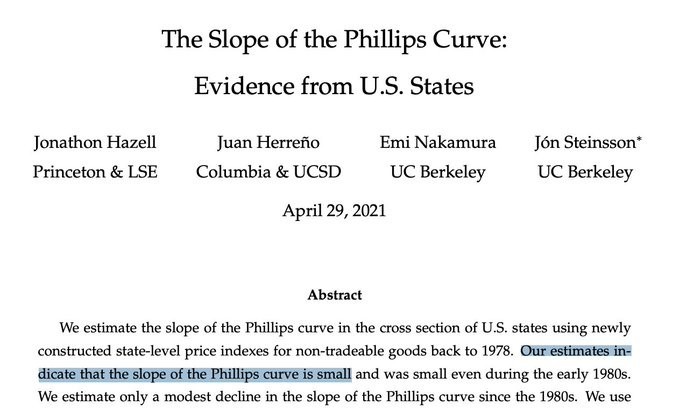

各理論は、相異なる価格について相異なる速度での調整を予測する。インフレがどのように上昇するか、および、どのようなミクロ的な特徴(例えば曲線の傾きや予想)が中心となるかについての推測も異なる。ミクロとマクロのデータはその2つの点で非常に有用であった。

しかし2021年前半は、ミクロの価格「ビッグ」データだけを見ていたら、様々な指標や変化するバスケットや基準効果*2や測定誤差に気を取られていたことだろう。(一部の人が実際にそうしたように)インフレが来るかどうかについて疑問を呈してさえいたかもしれない。理論によってそれが正される。

インフレのマクロ的見解は刺激策だけの話ではない。サマーズは初期の論説でそれに焦点を当てたが、論点はもっと幅広いものだった。4月のNBERマクロ年次大会*3で私が多様な聴衆にスライドを見せた時、人によって理論の好みは分かれた。

オースタン・グールズビーのライスらに対するツイート:

2) 2021年初めの刺激策の規模が主因だと言う厳密にマクロ的なインフレ見解は、それがベースラインとなる1年後には財政状況が大いにデフレ的になる、ということを含意していないか?

以上の理論において、インフレおよびその究極の原因が必ずしも悪いものとされていないことに注意されたい。理論によっては、インフレは必要な犠牲とされ、あるいは良いものとさえされている。ただし私は、ここで書いていることにおいて、「大したことないよチーム」と私が呼んでいる人々に対しては異を唱えている。そうした立場がもはや維持不可能であることを願いたい。

2022年以降のインフレはどうなるだろうか? それについては理論の見解は分かれている。データによってあるものが支持され、あるものは棄却されるだろう。討論が必要であり、不確実性は避けられない。それはいつもと同様だ。