FT Alphavilleのイザベラ・カミンスカが、非伝統的金融政策をmumps(=most unusual monetary policies;mumpsにはおたふく風邪の意味もある)と呼んだUBSのGeorge Magnusの論説に事寄せて、ここで紹介した自説をさらに解説している。

In short, the problem is not money availability but rather a lack of opportunities to deploy that money towards.

Think of it as the modern paradox of investment. We don’t necessarily need investments in things that produce more stuff. Rather, we need investment in companies that produce the same amount of stuff only more efficiently — or more stuff with less resources. There’s also the need to invest in big ideas, public infrastructure and utility projects, all of which are notoriously hard to squeeze profits out of.

It’s possibly one reason why the corporate sector has become so margin obsessed.

And here’s where the limits of growth debate comes in.

If there is a need in society, and a company moves to service that need, the company will usually derive a profit from filling that gap. (Unless it’s infrastructure-based in which case it’s about covering one’s costs and ensuring enough income can be generated to maintain operations.) So it makes sense to redirect today’s available capital, labour and output from an investor — who has no need for those things today, but believes will need more of those things tomorrow — to a company or entrepreneur, and reward the investor with additional output tomorrow.

Throughout history, bankruptcies have been caused by companies that were not able to keep those promises to investors in the future — mostly because the things they were making were less needed than anticipated.

・・・

However, the sooner the world realises that the old debt rules don’t necessarily apply to economies that to this day cannot justify delayed consumption — because there is more than enough capacity and output to go round, and there is no need to consume less today in order to ensure more output tomorrow — there isn’t the same importance attached to ensuring that old investor promises are kept sacrosanct.

・・・

After all, what does the number of promises in the economy matter, when there is more than enough goods and services to go round?(拙訳)

つまり、問題は資金の利用可能性ではなく、その資金を投入する機会の不足にある。

これは現代における投資のパラドックスと考えられる。我々は、もっと多くの財を生産するような事業への投資を必ずしも必要とはしていない。むしろ、同じ量の財を単にもっと効率的に生産する、ないし、より多くの財をより少ない資源で生産する会社に投資することを必要としている。気宇壮大な構想や公共インフラや公益事業に投資することも必要とされているが、それらの事業は利益を上げることが難しいことで悪名高い。

今の企業部門が利益を稼ぐことに囚われているのは、こうしたことが一因となっていると思われる。

そして、成長の限界に関する議論がここで顔を出すことになる。

もし社会に需要があり、企業がその需要を満たそうとするならば、当該企業はその需給ギャップを埋めることにより利益を上げるのが普通である(ただし、コストをカバーし、運用を維持するだけの収入を得るのが精一杯というインフラ整備事業を除く)。従って、今日利用可能な資本、労働と生産を、投資家――今日はそれらのものを必要としていないが、明日にはそれらのものをより多く必要とすると考えている投資家――から企業ないし起業家に振り向け、明日においてその投資家に追加的な生産で報いることには意味がある。

歴史を通じて、投資家に対するそうした将来の約束が守れなかった企業によって、破産が引き起こされてきた。約束が守れなかった理由の大部分は、彼らが製造した商品が予期したほど必要とされなかったことにある。

・・・

しかし、もはや消費を遅らせることが正当化できなくなった経済――正当化できなくなったのは、必要以上の生産能力と生産物が流通しており、明日の生産を増やすために今日の消費を減らす必要が無くなったためである――には必ずしもかつての債務のルールが当てはまらないということを世間が認識するや否や、投資家に対する以前の約束を神聖不可侵なものとすることの重要性は薄れた。

・・・

今や必要以上の財やサービスが流通しているというのに、経済における約束の数にこだわる意味がどこにあるのか、というわけだ。

なお、Magnusは、mumpsによって失われた利子所得の規模がオバマ政権の景気刺激策に匹敵することを指摘し、左手で与えたものを右手で奪いたもう、と揶揄しているが、これについてカミンスカは以下のようにコメントしている。

Since taking mumps away from the economy is not a practical solution, especially when the private sector refuses to spend, it stands to reason that the government must spend on behalf of the economy instead.

(拙訳)

mumpsを経済から取り除くのは現実的な解決策とは言えない――民間部門が支出を拒んでいる現在は特にそうだ――ので、代わって経済を支えるために政府が支出しなければならない、というのは理に適っている。

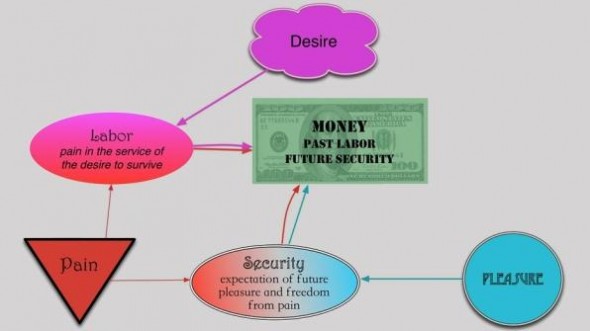

カミンスカはまた、こちらのエントリで、スピノザのいわゆる3つの感情――苦痛、喜び、欲望――に貨幣が結び付いている、というエマニュエル・ダーマン(Emanuel Derman)の論考に事寄せて、mumpsへの反発について以下のように考察している。

The conclusion Derman comes to is that money’s link to pain is crucial to determining its value.

In the current context, that makes for a rather striking insight.

Is the crisis the result of money having become detached from pain? What’s more, do financial bailouts, QE3, zero-interest-rate policies and easily printed money only detach money ever further from this historical link to suffering? And is this why such policies are currently drawing so much scrutiny and contempt?

As Derman notes:

Fiat money involves only pleasure and desire, but omits the recognition of pain.

In which case… are austerity policies more about an innate social need to reattach pain to money than a rational economic cure?

(拙訳)

ダーマンが到達した結論は、貨幣が苦痛に結び付いている*1ことが、その価値を決定するに当たって決定的な役割を果たす、というものである。

現在の状況に鑑みると、そのことは非常に驚くべき考察をもたらす。

危機は貨幣が苦痛から切り離された帰結として生じたのだろうか? また、金融機関の救済やQE3やゼロ金利政策や貨幣がいとも簡単に増刷されることは、歴史的な貨幣と苦痛とのつながりをさらに疎遠にしてしまうだけに終わるのだろうか? そして、そのことが、それらの政策が現在あれほどの厳しい目と軽蔑の眼を向けられている理由なのだろうか?

ダーマンは不換紙幣には喜びと欲望しかなく、苦痛の認識を切り落としてしまった。

と述べたが、そうしてみると…緊縮政策というのは、合理的な経済的処置というよりは、社会が貨幣に再び苦痛を結び付けることを本来的に必要としている、ということなのだろうか?

ちなみにこちらのFT Alphavilleまとめエントリでは、昨日紹介したボードリヤールエントリへのリンクと併せて、「イジーが市場の将来について哲学的になっている…(Izzy waxed philosophical about the future of markets…)」という(同僚への冷やかしのようにも読める)寸評と共に上の2番目のエントリにリンクしている。

このはてぶにも書いたことだが、金融市場周りの機能論を論じるに留まらず、このように経済学や哲学も踏まえて重層的な考察をするのがこの人の魅力であり、日本の金融ジャーナリストにはまず見られない特長である、と言えるだろう(もちろん、一歩間違えばただの衒学者になってしまう危険性と背中合わせではあるが)。

*1:ここでは貨幣を手に入れるための労働の苦痛を指している。下図参照。