というNBER論文が上がっている(ungated版へのリンクがある著者の一人のページ)。原題は「Organized Crime and Economic Growth: Evidence from Municipalities Infiltrated by the Mafia」で、著者はAlessandra Fenizia(ジョージワシントン大)、Raffaele Saggio(ブリティッシュコロンビア大)。

以下はその要旨。

This paper studies the long-run economic impact of dismissing city councils infiltrated by organized crime. Applying a matched difference-in-differences design to the universe of Italian social security records, we find that city council dismissals (CCDs) increase employment, the number of firms, and industrial real estate prices. The effects are concentrated in Mafia-dominated sectors and in municipalities where fewer incumbents are re-elected. The dismissals generate large economic returns by weakening the Mafia and fostering trust in local institutions. The analysis suggests that CCDs represent an effective intervention for establishing legitimacy and spurring economic activity in areas dominated by organized crime.

(拙訳)

本稿は、組織犯罪が浸透した市議会解散の長期的な経済的影響を調べた。イタリアの社会保障記録の母集団についてマッチングした差の差分析を適用して我々は、市議会解散(CCD)によって雇用、企業数、および産業用不動産価格が高まることを見い出した。その効果はマフィアが支配的な部門、および、現職の再選が少ない地域に集中的に表れた。解散は、マフィアを弱め、地域の制度に信頼を醸成することで大きな経済的リターンをもたらす。本分析が示すところによれば、組織犯罪が支配する地域で合法性を確立し、経済活動を促進する上で市議会解散は効果的な措置である。

市議会解散とは耳慣れない制度だが、導入部ではその制度と研究内容について以下のように説明されている。

Following allegations of Mafia infiltration in the local government, the central government dismisses the entire political apparatus of the municipality including the mayor and the city council. It then appoints a team of commissioners who administer the municipality for about two years with full legislative and executive powers until new elections occur. CCDs represent a unique policy used by the central government to regain control and legitimacy in areas where corruption was so pervasive that the Mafia de facto ran the local government.

We study the economic impact of 245 CCDs between 1991 and 2016 using a matched difference-in-differences design applied to rich administrative data on workers, firms, real estate prices, and public finances. We compare treated municipalities subject to CCDs to observationally similar untreated municipalities. Because of a strict procedure designed to limit its potential for abuse, CCDs are not triggered by poor economic performance. Consistent with that, there is no evidence of differential pre-trends between treated and control units over a variety of outcomes, lending credibility to the research design.

(拙訳)

地方政府へのマフィア浸透の申し立てを受けて中央政府は、市長と市議会を含め、地方自治体の政治組織全体を解散する。その後、中央政府はコミッショナーのチームを任命し、彼らが約2年間、新たな選挙が実施されるまで、完全な立法権および執行権を以って地方自治体を運営する。CCDは、腐敗が進んで事実上マフィアが地方政府を運営している地域において、中央政府がコントロールと合法性を取り戻すために用いるユニークな政策である。

我々は、マッチングした差の差分析を、労働者、企業、不動産価格、および財政の豊富な行政データに適用して、1991年から2016年に掛けての245のCCDの経済的影響を調べた。我々はCCD対象となった地方自治体の処置群を、観測値において類似している対照群の地方自治体と比較した。濫用の可能性を制約するための厳格な手順により、CCDは経済的なパフォーマンスが悪いことでは発動されない。そのことと整合的に、処置群と対照群の間では様々な結果について事前のトレンドの差異の証拠は見られず、研究方法に信頼性をもたらしている。

本文では制度がさらに以下のように詳説されている。

In response to the Mafias growing influence on local governments in the 1980s, the Italian parliament introduced a policy to dismiss city councils in 1991 (D.L. 31/05/1991 n. 164). If local governments appear to be under the influence of the Mafia, the law permits the central government to replace the mayor, executive committee, and city council with external commissioners (Commissari Straordinari) composed of experienced career civil servants from other areas. With full executive and legislative powers, these commissioners run the municipality for 24 to 36 months until new elections occur. This law is arguably the governments most aggressive policy tools to fight organized crime (CNE, 1995), and it aims to prevent future corruption by severing the ties between criminal organizations and the local government.

CCDs are typically initiated due to unrelated police investigations. However, the evidentiary bar is lower than for prosecution. Rather than looking for incontrovertible evidence of illegal activity, the Ministry of the Interior looks for connections between local politicians and organized crime, many of which occur during routine police investigations. Other times, the CCD is triggered by actual crimes such as extortion, drug and arms trafficking, money laundering, vote buying, and collusion in public procurement. It is not triggered by poor municipality financial performance or by inefficiencies and delays in public procurement.

To limit the possibility of arbitrariness or delays, the law establishes a very rigid procedure that governs the dismissal of the local government from the emergence of evidence to the final decision. Evidence of connections between elected public officials and the Mafia is first reported to the prefetto, the provincial representative of the Ministry of the Interior. The prefetto then forms a commission (Commissione d'Accesso) that investigates the allegations and issues a report within three months. In consultation with the cabinet, the interior minister uses the report to make a final decision on the dismissal, which is publicly decreed by the president in the Gazzetta Ufficiale, the government's official journal. Although the central government might in principle use this procedure to take over municipalities run by political opponents, Mete (2009) shows that the central government is not more likely to dismiss a city council when the mayor is affiliated with the opposition compared to when she is affiliated with the coalition in power.

Reviewing official reports of the interior minister to Parliament, external commissioners typically implement four types of interventions. First, they freeze all investments in new projects while reviewing the municipality's financial situation and scrutinizing procurement contracts, permits, and business licenses. Second, they revoke public procurement contracts, permits, and business licenses if they appear to have been obtained illegally or by means of connections to organized crime. Third, they change the municipal governments personnel practices. The official reports show that municipality bureaucrats are often poorly qualified and occasionally uncooperative. To professionalize the local bureaucracy, the commissioners often mandate training for employees. They also hire temporary workers for understaffed sites. Finally, they try to gain the trust and support of local communities. For example, they provide services such as free job training and local infrastructure investment.

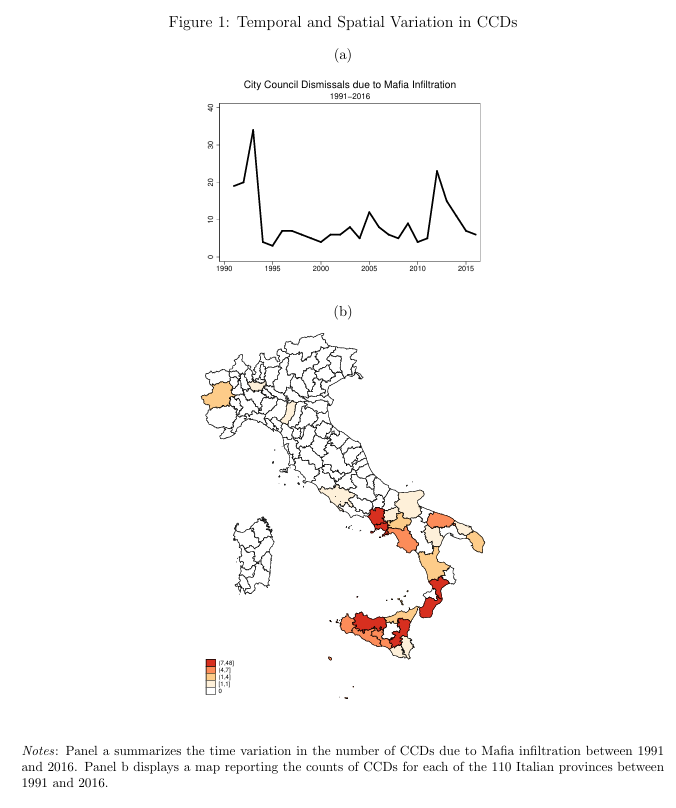

Since its introduction in 1991, 245 different municipalities have been subject to the CCD; 151 municipalities experienced one dismissal, 35 experienced two, and 8 experienced three. Multiple dismissals are indicative of the challenge of severing the very deep infiltration of organized crime into local government. Figure 1a plots the annual frequency of CCDs from 1991 to 2016. The spike in 1993 reflects the reaction to the terrorist attacks of Cosa Nostra in the early 90s, and the spike in 2012 coincides with Monti succeeding Berlusconi as prime minister. The government dismissed 23 municipal governments as part of the Monti governments agenda to implement structural changes to Italian institutions. Figure 1b illustrates the geographic variation of affected municipalities. CCDs are concentrated in Southern Italy, where the Mafia emerged at the end of the 19th century (Acemoglu et al., 2019). However, northern regions such as in Piedmont, Lombardy, and Liguria are not immune to Mafia infiltration (Dipoppa, 2021).

(google翻訳を適宜修正)

1980年代に地方政府に対するマフィアの影響力が増大したことを受けて、イタリア議会は1991年に市議会を解散する政策を導入した(D.L. 1991/05/31 n. 164)。地方自治体がマフィアの影響下にあると思われる場合、法律により中央政府は、市長、執行委員会、市議会を、他地域からの経験豊富なキャリア公務員で構成される外部コミッショナー(Commissari Straordinari)に置き換えることが認められている。これらのコミッショナーは完全な行政権と立法権限を持ち、新たな選挙が行われるまでの24~36 か月間自治体を運営する。この法律はおそらく政府が組織犯罪と戦うための最も積極的な政策手段であり(CNE、1995)、犯罪組織と地方自治体との関係を断つことによって将来の汚職を防ぐことを目的としている。

CCD は通常、無関係な警察の捜査をきっかけとして開始される。ただし、証拠のハードルは訴追よりも低い。内務省は違法行為の動かぬ証拠を探すのではなく、地元の政治家と組織犯罪とのつながりを探しており、その多くは警察の日常的な捜査中に発覚している。また、CCD は、恐喝、麻薬や武器の密売、マネーロンダリング、票の買収、公共調達における共謀などの実際の犯罪によって引き起こされることもある。 CCDは、地方自治体の財政状況の悪化や公共調達の非効率性や遅れによって発動されるものではない。

恣意性や遅延の可能性を制限するために、法律は、証拠の出現から最終決定までの地方政府の解散を管理する非常に厳格な手順を定めている。選挙で選ばれた公僕とマフィアとの関係の証拠は、最初に内務省の州代表であるプレフェットに報告される。 次にプリフェットは、申し立てを調査し、3か月以内に報告書を発行する委員会 (Commissione d'Accesso) を設立する。 内務大臣は内閣と協議の上、この報告書を用いて解散に関する最終決定を下し、 政府公報であるGazzetta Ufficialeで大統領によって公けに宣告される。 原理的には中央政府が政敵の運営する自治体を乗っ取るためにこの手続きを利用する可能性があるが、Mete (2009) は、市長が野党に所属している場合でも、市長が連立政権側に所属している場合と比べて中央政府が市議会を解任する可能性が高くないことを示している。

内務大臣の議会への公式報告書を検討し、外部コミッショナーは通常 4 種類の介入を実施する。まず、自治体の財政状況を見直し、調達契約、許可、営業許可を精査しながら、新規プロジェクトへのすべての投資を凍結する。 第二に、公共調達契約、許可、営業許可が違法に、または組織犯罪とのつながりによって取得されたと思われる場合、それらを取り消す。 第三に、自治体の人事慣行を変える。 公式報告書によると、地方自治体の官僚は資質が低いことが多く、非協力的な場合もある。地方官僚の専門化を図るため、コミッショナーは職員に研修を義務付けることが多い。人手不足の現場では臨時職員も雇っている。最後に、彼らは地域社会の信頼と支援を獲得しようとする。たとえば、無料の職業訓練や地域のインフラ投資などのサービスを提供する。

1991 年の導入以来、245の相異なる自治体がCCD の対象となった。解散を一度経験した自治体は151、二度経験した自治体は35、三度経験した自治体は8だった。複数回の解散は、地方自治体への組織犯罪の非常に深い浸透を断ち切ることの難しさを示している。図1aは、1991年から2016年までのCCDの年間発生頻度をプロットしている。1993年の急増は 90年代初頭のコーサ・ノストラのテロ攻撃*1への反応を反映しており、2012 年の急増はモンティがベルルスコーニ首相の後継者となった時期と一致している。政府は、イタリアの制度の構造改革を実施するというモンティ政権の計画の一環として、23の地方自治体を解散した。図1bは、影響を受けた自治体の地理的バラつきを示している。CCD は19 世紀末にマフィアが出現した南イタリアに集中している (Acemoglu et al., 2019)。しかし、ピエモンテ州、ロンバルディア州、リグーリア州などの北部地域もマフィアの浸透を免れないわけではない(Dipoppa、2021)。

ちなみにシカゴ大で開催されたこの論文の3年前のプレゼンでは、組織犯罪が跋扈する中南米への参考に供するという観点で講演が行われたようである。

*1:cf. コーサ・ノストラ - Wikipedia。