昨日紹介したメンジー・チンのエントリに、デビッド・ベックワースが以下のようなコメントを寄せていた。

Menzie:

Something that I wrestle with is the question of whether all output gaps (assuming they are measured correctly) are the same. Let me explain. Let's say there is a negative output gap. If it were created by a negative AD shock then it then the notion of an output gap as it is normally used makes senses (i.e. policy should aim to close the gap). What if, however, the negative output gap were created by a positive AS shock, say a surge in the productivity growth rate. It is far from clear to me that this creates the same problem as one from a negative AD shock.

Any thoughts? Thanks in advance.

(拙訳)

メンジー:

私が悩んでいるのは、GDPギャップを(正確に測定されたものとして)等し並みに扱ってよいのか、という問題だ。負のGDPギャップを例に取って説明しよう。それが負の総需要ショックによってもたらされたならば、通常のGDPギャップの概念で扱うことに問題はない(即ち、政策はそのギャップを埋めることを目指すべきだ)。しかし、もしその負のGDPギャップが、生産性成長率の急上昇のような正の総供給ショックによってもたらされたならば、どうだろうか。その場合の問題が負の総需要ショックによる場合と同じだとは私には到底思えない。

これについてご意見をお聞かせいただけると有難い。

これにチンは以下のように答えている。

David Beckworth: That's an interesting question. From the perspective of the model, and using an objective function expressed in terms of the output gap w/quadratic loss, I don't think that one should care how the gap arises.

On the other hand declining marginal utility of consumption might suggest that one cares more about deficient AD as opposed to higher AS. That's an informal thought...

(拙訳)

デビッド・ベックワース、面白い質問だ。モデルの観点から言えば、また、GDPギャップについて二次関数的な損失を組み込んだ目的関数を用いるならば、人々がGDPギャップの起因についてこだわるとは私には思えない。

ただ、消費の限界効用逓減を考えるならば、人々は総需要の不足を総供給の上昇よりも気にすると言えるのかもしれない。ほんの思いつきだが…。

このようにチンは専ら消費者の効用という観点から返事しているが、ベックワースはむしろ中銀の政策対応という面での回答を期待していたと思われる。というのは、先月24日のブログで彼は以下のように書いているからだ。

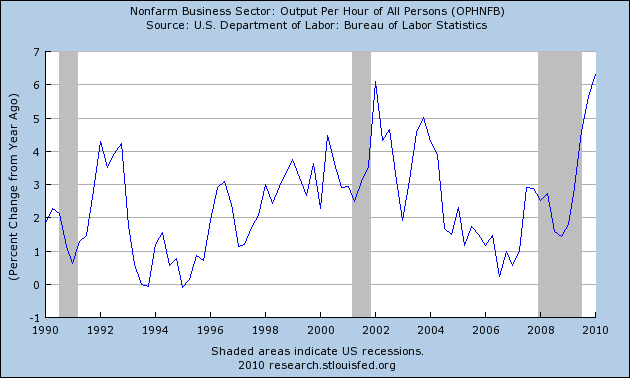

As I noted in my previous post, this spike in the productivity growth rate may be why the unemployment rate has been remained so high. If, in fact, this productivity surge is the cause of the downward price pressures then here is another case that illustrates why it is important to distinguish between deflationary pressures arising from a negative aggregate demand shock versus those coming from positive aggregate supply shocks. I have written about the importance of this issue before, especially with regards to the 2003 deflation scare.

(拙訳)

前回のエントリに書いたように、この(=上記グラフの2009年第4四半期以降の)生産性成長率の上振れが、失業率があれほど高水準に留まっている理由かもしれない。この生産性の上昇が本当に物価に低下圧力を掛けているならば、負の総需要ショックによるデフレ圧力と、正の総供給ショックによるデフレ圧力を区別することの重要性を示すもう一つの例ということになる。この問題の重要性については以前書いたことがあり、特に2003年のデフレ懸念との関係について書いたこともある。

今回の景気回復において生産性上昇が高い失業率の継続につながっているのではないか、という話は以前にも紹介したが(ここ、ここ)、ベックワースは、その場合には需要不足の場合と同じに考えてはいけない、と主張しているわけだ。グリーンスパンは2003年にその過ちを犯し、今回のバブルを招いた、というのが彼のかねてからの見解である。上記でリンクしている昨年6/22のブログエントリでベックワースは、以下のように当時のFRBの対応を批判している。

...There is a real deflationary threat lingering over the U.S. economy in 2009.

With that said, there is an unfortunate irony to the current deflationary threat that can be traced back to 2003. Back then there was another deflationary threat that concerned the Federal Reserve (Fed). As a result, the Fed lowered the federal funds rate to what was at the time an historically low value of 1%. It held this short-term interest rate there for a year before gradually tightening. As we now know, this excessively-loose monetary policy was an important contributor to the buildup of the economic imbalances that eventually led to this economic crisis, including the current deflationary threat. In short, the fear of deflation in 2003 laid seeds for the deflationary threat of 2009.

What makes this an unfortunate irony is that this chain of events did not have to happen. For there was a big difference between the deflationary pressures in 2003 and the ones in 2009. In 2003 the deflationary pressures were driven by rapid productivity gains and were benign in nature. Moreover, nominal spending or aggregate demand was rapidly growing. There simply was no evidence of a malign deflationary threat as there is today and thus, there was no need for the Fed to drop interest rates so low for so long. I have documented these developments in previous posts...

(拙訳)

・・・2009年の米国経済には真のデフレ危機が迫っている。

ただ、現在のデフレ危機には、2003年に端を発する不運な皮肉が付きまとっている。当時もデフレ危機が存在し、FRBはそれに頭を悩ませていた。結果としてFRBは、当時としては歴史的に低い水準である1%までFFレートを切り下げた。その短期金利の水準は1年間継続され、その後徐々に引き上げられた。今や明らかになっている通り、この過度の金融緩和政策は、経済の不均衡が醸成される上で重要な要因となった。その経済の不均衡が今回の経済危機を招き、現在のデフレ危機につながった、というわけだ。つまり、2003年のデフレ懸念が2009年のデフレ危機の種を撒いた、ということになる。

これが不運な皮肉である所以は、こうした連鎖反応が起きる必要が無かった点にある。というのは、2003年のデフレ圧力と2009年のデフレ圧力には大きな違いがあるからだ。2003年のデフレ圧力は急速な生産性の上昇によってもたらされ、本質的に良性のものだった。しかも、名目支出や総需要は急速に成長していた。今日見られるような悪性のデフレ危機の証拠は当時は存在せず、FRBがあれほどの低金利をあれほど長く続ける必要性は無かった。このことは以前のエントリでも書いたことだ・・・

この昨年のエントリでベックワースは、現在のデフレ危機は本物だ、と書いているが、それから1年経って、生産性が大きく上昇したのでデフレ危機は去った、と結論付けたわけだ。

ただ、5/24のエントリで彼は、小売売上高の順調な回復とフィラデルフィア連銀の名目GDP予測サーベイを基に今や総需要も伸びていると述べたが、翌5/25エントリでは、それは早計に過ぎるのではないか、というライアン・アベントの指摘を受けて少し弱腰になり、名目GDPの先物市場があったらもっと直近の状況が把握できるのだが、と言い訳のようなことを書いている*1。実際、彼が強気の根拠とした小売売上高はその後反落したわけで、後知恵で金融政策の拙さを批判することと、現在の景気の状況をリアルタイムで的確に判断することは別物であることをいみじくも物語っているように思われる。