アンドリュー・ゲルマンが、英国心理学会(The British Psychological Society)の研究ダイジェストブログのある記事にいたく失望させられた、と書いている*1。

その記事にゲルマンが失望した理由は、統計的検定に関する基礎的な間違いを犯しているからである。記事を書いたのはWarren Daviesというイーストロンドン大学(UEL)の修士生だが、彼を責めはしない、とゲルマンは述べている。彼の非難の矛先は、むしろ、英国心理学会の看板を掲げたブログでこのような記事の掲載を許してしまった編集者に向けられている。

どこが間違っているのかもっと分かるように教えてくれ、というコメントに応じて、ゲルマンは以下のように簡潔に説明している。

The following statement from the above quote is false: "all statistical tests in psychology test the possibility that the hypothesis is correct, versus the possibility that it isn't."

No. The p-value is not the probability (or "the possibility") that the hypothesis is correct.

(拙訳)

上のエントリ本文で引用した文章のうち次の文が間違いだ:「心理学の統計的検定はすべて、仮説が正しい可能性と仮説が正しくない可能性を比較対照して検定している。」

そうではない。p値は仮説が正しい確率(ないし「可能性」)ではない。

元記事のコメント欄でも、その誤りに対して批判が数多く寄せられた(その結果、同記事は今は訂正されている)。そのうちのあるコメントでは、Jacob Cohenの論文「The Earth is round (p < .05)」にリンクしている。その論文の記述がこの点に関する説明としては最も分かりやすいように小生には思われたので、以下に引用してみる。

Why P(D|H0) ≠ P(H0|D)

When one tests H0, one is finding the probability that the data (D) could have arisen if H0 were true, P(D|H0). If that probability is small, then it can be concluded that if H0 is true, then D is unlikely. Now, what really is at issue, what is always the real issue, is the probability that H0 is true, given the data, P(H0|D), the inverse probability. When one rejects H0, one wants to conclude that H0 is unlikely, say, p < .01. The very reason the statistical test is done is to be able to reject H0 because of its unlikelihood! But that is the posterior probability, available only through Bayes's theorem, for which one needs to know P(H0), the probability of the null hypothesis before the experiment, the "prior" probability.

Now, one does not normally know the probability of H0. Bayesian statisticians cope with this problem by positing a prior probability or distribution of probabilities. But an example from psychiatric diagnosis in which one knows P(H0) is illuminating:

(拙訳)

なぜ P(D|H0) ≠ P(H0|D) なのか?

H0を検定する時には、H0が真の時にデータ(D)が生じる確率P(D|H0)を測定している。もしその確率が小さければ、H0が真ならばDは起こりそうもない、と結論できる。しかし、ここで本当に知りたいこと、常に知りたいことは、そのデータを前提とした場合にH0が真である確率、すなわち逆確率P(H0|D)である。H0を棄却する時には、例えばp < .01でH0がありそうもない、と結論付けたいわけだ。H0はありそうもないから棄却する、と言えるようにすることが、まさに統計的検定を実施する理由なのだ! しかし、それは事後確率であり、ベイズの定理を用いて初めて得られるものである。そして、そのためには、まず、実験を実施する前の帰無仮説の確率、すなわち事前確率を知る必要がある。

だが、普通はH0の確率が既知であることはない。ベイズ統計の学者たちは、事前確率ないし確率分布を仮定することによって、この問題に対処する。一方で、P(H0)が既知である精神病の診断の例は、この問題の理解に役立つだろう:

続いてCohenは、統合失調症の診断を例にとって以下のように説明する。

ここで

とすると、ベイズの定理より、

P(H0|D)

= {P(H0)×P(誤診|H0)} ÷ {P(H0)×P(誤診|H0)+P(H1)×P(正診|H1)}

= {0.98×0.03} ÷ {0.98×0.03+0.02×0.95}

= 0.607

となる。すなわち、P(D|H0)は3%であるにも関わらず、P(H0|D)――統合失調症と判定された人の中の正常人の割合――は60%に達する。

[9/11追記start]

Cohenはこの計算例を紹介した後で、以下のように書いている。

This extreme result occurs because of the low base rate for schizophrenia, but it demonstrates how wrong one can be by considering the p value from a typical significance test as bearing on the truth of the null hypothesis for a set of data.

(拙訳)

この極端な結果は統合失調症の事前確率が低いために生じているが、通常の有意検定のp値を、あるデータ集合における帰無仮説の真実性に関係していると考えた場合に、どれほどの間違いを犯し得るかを示している。

[9/11追記end]

なお、このCohenの論文にリンクしたコメンターKaj Sotala (Xuenay)は、Daviesが本文中でサイコロを2回振る例を出したのを引き合いに、以下のような応用例を示している。

- 正常なサイコロを2回振って6の目が続けて出る確率は1/36 ( P(D|H0)≒2.8% )。

- 今、10,000個のサイコロのうち9,900個は正常で、残りの100個は必ず6の目が出るものとする。従って、不正サイコロの割合は、P(H1)=1-P(H0)=1%。また、P(D|H1)=100%。

- その10,000個のサイコロに対し、2回振るという検査を掛けた場合、不正なサイコロは100個すべて検査に引っ掛かるが、同時に、正常なサイコロのうち9,900/36=275個が検査に引っ掛かる。従って、検査に引っ掛かったサイコロのうち275/375=73%が正常なものである。すなわち、P(H0|D)=73%。

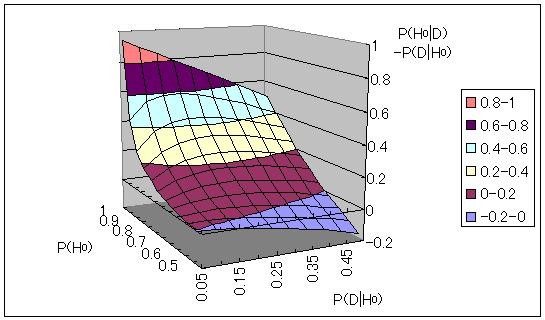

ちなみに、このサイコロの例において、P(D|H0)を5〜50%、P(H0)を50〜100%の範囲に取って、P(H0|D)とP(D|H0)の差を描画してみると、以下のようになる。

P(H0)が100%に近いとP(H0|D)とP(D|H0)の差は大きい。その差が小さくなるのは、P(D|H0)が5%前後の場合、P(H0)が50%近くまで下がった時であることが分かる。

[9/11追記]

本エントリに対し、wrong, rogue and booklogから以下のようなコメントを頂いた。

あ、いや、これAndrew Gelmanはそんなに難しいことを言ってはいない。単に、統計的検定での「有意水準」の概念が身についていないので、「p値」の使い方が間違っている、と言っているだけ。

もちろん、Gelmanのブログの読者らしくコメント欄のようにベイジアン的な説明を持ってきてもいいんだけれど、そんな必要は全く無い。

そうか、このトンチンカンなエントリをみるとhimaginary氏は統計学がイマイチなのか。

2点反論のコメントをしておく。

一つは、本エントリではゲルマンの批判はあくまでも前振りに過ぎず、主眼はあくまでもDaviesの記事とCohenの論文との対照にある、という点である。その点について書き方が悪い、という批判は甘んじて受ける(実際、書いている途中に、単に「H/T ゲルマンのブログエントリ」で済ませておけば良かったかな、と後悔したが、折角ここまで書いたのに消すのは勿体無い、ということでそのまま残したという経緯がある)。

そのCohenの論文の要旨には以下のように書かれている。

After 4 decades of severe criticism. the ritual of null hypothesis significance testing - mechanical dichotomous decisions around a sacred .05 criterion - still persists. This article reviews the problems with this practice, including its near-universal misinterpretation of p as the probability that H0 is false, the misinterpretation that its complement is the probability of successful replication, and the mistaken assumption that if one rejects H0 one thereby affirms the theory that led to the test. Exploratory data analysis and the use of graphic methods, a steady improvement in and a movement toward standardization in measurement, an emphasis on estimating effect sizes using confidence intervals, and the informed use of available statistical methods is suggested. For generalization, psychologists must finally rely, as has been done in all the older sciences, on replication.

文中の「near-universal misinterpretation of p as the probability that H0 is false」がまさにゲルマンを激昂させたDaviesの過ちであり、このCohenの16年前の論文は期せずしてそれへの反論になっている。小生は単にCohenの論文から、該当部分を引用したに過ぎない。従って、今回の問題を取り上げるに当たって、最初に「ベイジアン的な説明を持ってき」たのは小生でもDaviesの記事のコメンターKaj Sotala (Xuenay)(注:「Gelmanのブログの読者」ではない)でもなく、Cohenである。

また、ゲルマンは該当エントリの追記で以下のように書いている。

P.S. To any confused readers out there: The p-value is the probability of seeing something as extreme as the data or more so, if the null hypothesis were true. In social science (and I think in psychology as well), the null hypothesis is almost certainly false, false, false, and you don't need a p-value to tell you this. The p-value tells you the extent to which a certain aspect of your data are consistent with the null hypothesis. A lack of rejection doesn't tell you that the null hyp is likely true; rather, it tells you that you don't have enough data to reject the null hyp. For more more more on this, see for example this paper with David Weakliem which was written for a nontechnical audience.

この追記中に、この件についてもっと知りたければこちらを参照せよ、としてリンクされているゲルマン自身の共著論文を読むと、カナザワサトシ氏の分析を批判するに当たって、まさに「ベイジアン的な説明を持ってきて」いる(イントロダクションに続く最初の小題がいきなり「Classical and Bayesian Inference for Small Effects」となっている;下記引用も参照)。

Using this as an example, we consider how the problem can be framed in two leading statistical paradigms: classical inference, which is based on hypothesis testing and statistical significance, and in which external scientific information is encoded as a family of “null hypotheses”; and Bayesian inference, in which external information is encoded as a “prior distribution.”

これを読むと、統計的検定の問題を説明する時に「ベイジアン的な説明を持って」くるのはそれほど「トンチンカンな」ことではなく、ゲルマン自身が、むしろ通常の手順の一環として考えているように見える。